Everyone has their own reaction when discovering wrong data. It might start with a double take or maybe an itching feeling that the number should be a higher. However it starts, it usually leads to an investigation to discover what went wrong. While this is a very normal reaction, I offer an alternative. Before turning over every stone in your ETL, ask a few questions to discover if your “wrong” data really is wrong.

In this post I explore what wrong means when it comes to data (spoiler alert: it is not black and white). I also offer a few tricks to diagnose which of the buckets of wrong your problem falls into. Yes, this approach may add an extra step or two in your process, but it can also save a day of work trying to fix something that isn’t even broken.

Begin with questions

Whoever came up with the saying “measure twice, cut once” probably was not thinking about troubleshooting the outputs of a reporting system. Origin aside, the saying is applicable when diagnosing the cause of wrong data – make sure you know what problem you are investigating before you start investigating.

The two questions I find most helpful to answer before beginning my investigation are:

- What results would I / you expect to see?

- Where would I / you check this number to know it is correct? (i.e., source of truth)

These questions are incredibly helpful because they help to identify the reference point that the consumer of the data uses to determine if the data is correct. This leads me to the thesis of my post – wrong does not actually mean wrong, it means a mismatch between expectation and reality. This means that for data to be viewed as wrong there is an issue with expected numbers, presented numbers or potentially both at the same time.

In additional to diagnosing where the issue lies (i.e., expectation or reality) these questions will also help you diagnose the degree to which expectation and reality are out of sync. If your stakeholder expects to see the number 23 and -23 is displayed it is potentially a simpler fix (find the negative you dropped) than seeing the number 1.35.

After evaluating the answers to the questions listed above, you will most likely find you land in one of the following three buckets of “wrong”:

- The data is confusing (but not wrong)

- The stakeholder is using a faulty source to “check” the data (which is not wrong)

- The data really is wrong

The data is confusing (but not wrong)

This is the most common use case I have come across. Confusing data often occurs when the business logic is not surfaced to the stakeholder as it is hidden behind a reporting layer or occurs deep in the transformation layer.

Let’s take the KPI “sales”, for example. You can calculate sales as gross or net, at time of sale or at time recognized following GAAP, including returns or not – the variants are endless and often unique to the team and / or company. Ultimately, it is best to get the entire organization speaking the same language when it comes to KPIs, but that is a large enough topic for a standalone blog post (or book!). At minimum, I suggest exposing the definitions of your most important KPIs in some sort of data dictionary (perhaps as part of your data warehouse SLA).

Another potential cause of confusion could be time delays. Most reporting tools and data warehouses do not display real-time data. This can lead to a situation where there is no confusion about the metric definition, just confusion about how current the data is. For example, data in most website reporting tools (e.g., Google Analytics) is delayed by a few hours (I have seen websites with heavy traffic see delays as great as 12 hours). Stakeholders may want to look at the traffic volume of a big press hit or a new website feature and be confused when the data does not appear to be there.

Notice cause of confusion in these cases is in how the data is presented or taught to the stakeholder. Sending the data in an email, or building a report without providing context (metric definition, data freshness) can sometimes do more harm than good.

The stakeholder is using a faulty source to “check” the data

Remember, wrong is relative and in this case, it is relative to data that is itself incorrect. One place you might see this is in web traffic statistics. Suppose you have an internal, server-side tracking system capturing site visits as well as an external tracking tool. On your way to the office an email hits you: “Google Analytics traffic looks higher than our internal tracking.” There are a number of regularly occurring reasons this could happen.

The most common is normal variance between data sources. In the example above you are comparing a near lossless data source (server-side tracking) with a fallible data source (client-side javascript tracking). The client-side session count could be lower because of ad blockers or javascript not loading due to a heavy website / slow internet connection. Alternatively, the server-side session count could be lower because your 3rd party client-side tracking tool automatically filters out bots and other suspect traffic.

In the case of normal variance, the different between the data sources typically falls in a predictable range (if it doesn’t you may want to run through the web analytics checklist). Once you have determined acceptable variance use it as a lens through which you evaluate whether data is actually wrong. Demonstrating the historical variation (through data) can help to defuse wrong data conversations. Setting the expectation up front that the systems will have different numbers can help prevent wrong data conversations before they start.

You may, however, come across cases when the internal traffic data is significantly lower than your external web tracking tool. There is the very real possibility to consider that the internal tracking tool could have issue. Perhaps the server crashed last night or was overwhelmed by the amount of traffic that was passing through the system during a traffic spike. While your internal services may be robust, it is always important to consider that all systems can break – internal and external.

The data really is wrong

Sometimes data really is wrong. It is a result no one likes, but considering the complexity of translating your transactional database to a star schema and then calculating business KPIs, it is expected. I like to think my goal is not to prevent all errors, but to make sure the errors that do occur are small and caught / resolved quickly. To improve your odds of quickly finding errors, build your data quality flywheel – a culture where everyone feels responsible for data quality.

Conclusion

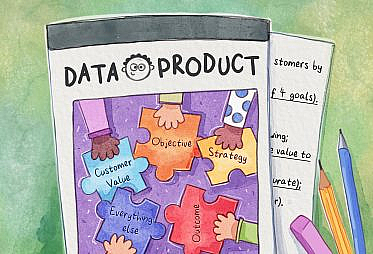

Sometime wrong data is wrong and sometime it is actually right. Before embarking on a journey to the center of your data stack do your due diligence to understand why your stakeholder (or you) thinks the data is wrong. Armed with this information, apply the appropriate solution – teaching your stakeholder or fixing the data product.

Remember “wrong” data, regardless of whether the data is wrong or not, is your responsibility. If stakeholders look at a report and get the wrong idea of the business logic under the hood, that is as much of a problem as the math being wrong.

Reporting tools are great for a business (see: Reporting is a Gateway Drug), but with sharing information comes the responsibility to help people make sense of it. If you are digging into the data every day, you are all too familiar with the imperfections of the data stores you are touching. Just remember not everyone is as familiar with the data as you!