While efforts to build a data dictionary are often undertaken out of a zeal for documentation that we would normally applaud, in practice data dictionaries and data catalogs end up being a large maintenance burden for little actual value, and tend to very quickly become out of date.

Instead of investing in building out traditional data dictionaries, we recommend a few different approaches for achieving the same goals in ways that are less burdensome to maintain and better serve the original objectives as well.

What is a data dictionary?

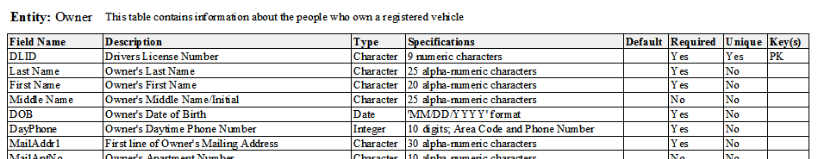

In this post we’ll use the term “data dictionary” to describe a range of products that include both “data dictionaries” and “data catalogs”. In general, we’re referring to documents that contain metadata about tables in a data warehouse – most commonly, they have one section per table with one row per column including information like the column-name, the column-type, any relevant foreign-keys, and a brief description of the column. Sometimes there will be additional metadata about the source of the table (a source system or potentially a person).

Why are data dictionaries created?

Listen. There’s no activity the two of us like better for enjoying a beautiful spring Saturday than sitting down at our desk, cracking open a cold Kombucha, and writing some damn documentation. While we definitely understand the desire to document-all-the-things, we also believe that it is important to find the right documentation and tools for the goals that you want to achieve. People tend to embark on the data dictionary journey with a few varied and vague goals in mind. They want to 1) enable more data exploration, 2) codify a single source of truth for data definitions, and 3) document the provenance of particular pieces of business logic.

These are all great goals! However, we do not believe that data dictionaries are the best tool for achieving any of these objectives. We will talk a bit about why we do not believe that data dictionaries, as traditionally constituted, work very well before diving into alternative ways to achieve those goals.

What goes wrong with data dictionaries?

With your traditional data dictionary, you start small and simple. Maybe just documenting the columns of your core tables, or the definitions and business logic behind your top three KPIs.

But new use cases are always coming up, new ways of looking at data and measuring success (that you really want to standardize) – and so the list grows.

If your KPIs aren’t just pulling from a single table or a single system, now you need to start documenting how different sources join together in a wild mess of foreign key relationships. Maybe you even create some ERDs – pictures speak a thousand words after all.

And everything is great…until you run into the issue of different audiences:

- Non-technical business users: Just want the data, or at most, a high-level summary of the KPIs and why they’re important.

- Business analysts: Want the data, but also the business logic behind it, and probably the data process used to populate the source and/or the relevant context.

- Data scientists / Engineers: Just want the column-level metadata, relationships, and instructions to query the raw data correctly – “I can write my own SQL/Python, thanks.”

Which means that realistically, to solve everyone’s use case, you’ll need to write three versions of documentation (or one, very large version) for any given piece of data. Not fun.

But even if you’re willing to go down that path, eventually something will change. Maybe your definition of NPS or Conversion just shifted a little bit (as we all know, business logic can be extremely slippery), and all of a sudden you have to update not only your data model and dashboards + reports, but also 3 documents and 2 diagrams.

The maintenance burden very quickly grows into a scalability issue, and a serious blocker to the development / iteration speed of the entire data team. Not only does maintaining documentation slow you down, but once the documentation starts to slip (as it inevitably will) the consumers of the data dictionary will begin to lose trust in it, and you will be investing time in maintaining this document that people do not even trust (and therefore will not use).

As a result, the heroes who start down the path of the perfect data dictionary often end up with a solution that:

- Is hard to maintain

- Is hard to use, and doesn’t answer everyone’s questions

- Is generally out-of-date (in one way or another)

- Ends up getting deprecated

Fortunately, we have better ways of achieving the same goals with less maintenance burden – a win-win.

What are the other options?

We believe the best way to approach the problem is by using the right tools for the right job – providing appropriate solutions for users at each level of the data literacy curve.

For the non-technical business user:

They’re really looking for an actionable, easy-to-use, single source of truth. Data – signed, sealed, and delivered. In our opinion, the best solution involves showing rather than telling: a well-architected and well-curated BI platform. In general, we believe that non-technical business users should not be writing SQL and therefore should not use a data dictionary as traditionally constituted.

We do not want to go into a full-fledged comparison between BI platforms here, but whatever your stack may be, here are the key features you’ll want to keep an eye out for:

- Single Source of Truth

- Data used to drive business decisions comes from a single system/platform

- Business logic is centrally defined, curated, and easily reproducible

- KPIs are clearly defined, well-organized, and shared across the organization

- Ad-hoc Exploration

- High-level KPIs are rarely actionable – so allowing users to take the next step in slicing + dicing, discovering, and drilling down into the data is critical

- Right Level of Abstraction

- Naively exposing every piece of data will create a difficult, confusing, and intimidating user experience

- Develop a curated, properly labeled, easy-to-navigate dataset (with complex joins, data cleaning, etc. abstracted away from the end user)

- Balance between governance and democratization

- Do you allow people to save their own reports/dashboards? Define their own dimensions / measures / transformations?

- Self Documenting Code

In a good BI tool, it should be easy for business users to find existing reports/dashboards that they can easily modify (or leverage as a starting point for additional exploration). The tool should provide guard-rails that help them avoid making common mistakes, and provide enough metadata (either through tool-tips or text descriptions) to help business users both find what they are looking for and avoid common pitfalls. The difference between these tool-tips and a data dictionary is that the tool tips live with the data as they are actually used by business users, and reflect the post-business-logic description of the entity which is generally much more useful to end-users1If you’re interested in upgrading your Looker tool-tips, the good folks at WW (formerly weight watchers) have released some neat tools to help maintain good descriptions..

If your BI tool has these qualities, then your business users will not need (or wouldn’t get any value out of) a data dictionary. Since the BI tool should help business users answer business questions, your business users should not have to know anything about the underlying data structures in order to achieve their goals. If you find your business users asking for a data dictionary, you should be thinking about building them better tools rather than just documenting the current suboptimal system.

Depending on the size of your team, the structure of your organization, and the complexity of your database, you may need to augment your BI tool with some additional tooling in the form of a wiki or knowledge-base (more on this below). For your non-technical users this is best used as a reference for “who is the expert” that they should go talk to if they want to get started in a new domain area.

For the business / data analyst: For the people in your organization who are rolling up their sleeves and diving into the data, there should be two sources of documentation that are most relevant:

- A self-documenting and searchable code-base

- A knowledge-base or wiki of high-level descriptions

The first place an analyst should look when trying to understand a table or column is in the code base that creates and manages that table or column. If, for example, you are using Looker as your BI tool on a dbt code-base, your analysts should be able to quickly and easily search those code bases to find the correct sections of code. If your code base is well-architected and you follow best practices for programming style and readability, it should be straightforward for the analyst to review and comprehend the relative logic. If your analyst cannot review and comprehend the logic, you should consider refactoring your code base or implementing more stringent code-review practices.

For the types of knowledge that are not easy to see in the code itself, it can be helpful to have a knowledge base that people can review for high-level information about a given concept. This documentation should not be a simple catalog of “what is in the data warehouse” but rather should include information about the who, what, and why behind broad concepts in the business:

- What is (NPS, ARR, Conversion, insert your concept here), how do we define it, how is it made (data processes, business logic), why is it important, and what are the next steps?

- Important context and history (“this is the story of why it takes 5 joins to connect our historical email data to our coupon code system”).

- Any potential “gotchas” (“we know that this logic is incorrect for some number of users, but the last time we checked it impacted less than 1% of users and so we ignored it”).

Between these two sources of information, analysts should have everything they need to understand and make use of the data they have.

For the data scientist / engineer:

For the most technical folks on your team, you can add some additional tooling that can help them find information that will be most useful to them. In addition to the self-documenting code-base (which is easily the most important concept in this blog post), you can think about adding:

- Knowledge-repo: This tool is used to keep track of analyses that have happened in the past, and can be a great resource for both analysts and data scientists to see 1) example uses of certain data sets and 2) analyses that are related to the topic they are working on. Seeing how someone else used a given table is often the best way for someone to understand its intricacies.

- Programmatically-generated ERDs: rather than maintaining these types of documentation by hand, programmatically-generated ERDs or data-heritage DAGs (from a tool like dbt or airflow) are the best way to ensure that your documentation actually matches your code.

- Architecture Design Documentation: this is often an artifact of the development process that includes an in-depth description of requirements, technical decisions made, architecture, etc.

Other important things to keep in mind:

- You need a strong data organization to maintain these different avenues of documentation

- You need a data-driven culture of cross-functional collaboration to make all of the pieces fit together

What are data dictionaries useful for?

There are two use-cases where having something like a data dictionary can be valuable:

- If you are a data-as-a-service (DaaS) provider, then your data dictionary is effectively documenting your API and will be critical to your clients

- For compliance / security reasons, you have complex restrictions on who can access different parts of your warehouse

These two use-cases are pretty niche, and we do not believe they apply to most internal-facing analytics teams. The second use-case is a bit tricky because what you want to build is not a “data dictionary” as we defined above (with “helpful” metadata about tables and columns) but rather an access-spec which can hierarchically define access to different parts of a warehouse (at the schema, table, column, and row level). We have some ideas on how you might build an effective tool for this, so if you’re working on something like that, please reach out!

Conclusion

Overall, we think that data dictionaries tend not to be very useful, and a data team’s time will be better spent maintaining a well-organized code-base that is self-documenting and providing well-designed BI tools to end-users that do not require much documentation. Where possible, teams should make use of tools for automatically generating documentation directly from code in order to prevent concept drift.

- 1If you’re interested in upgrading your Looker tool-tips, the good folks at WW (formerly weight watchers) have released some neat tools to help maintain good descriptions.