Often, Data and Analytics teams go under-utilized in their organization because they can not collaborate effectively with the broader Technology and Software Engineering teams.

By designing software following the “code as configuration” pattern, software engineers can enable and empower Analytics teams to work independently: both taking advantage of their technical skills and removing drudge-work responsibility from the Software Engineering team — a win-win.

People working on software infrastructure will be familiar with the terms ‘configuration as code’ and ‘infrastructure as code’ which refer to best practices for working with cloud-computing infrastructure in a way that is repeatable, automatable, and version controlled. This allows engineers to treat aspects of the development cycle that had historically been outside of the purview of version control systems (like provisioning and maintaining hardware) with the same processes and tools they use to manage their application code.

In this post I discuss an inversion of that idea which I refer to as code as configuration that can help Analytics and Sotware Engineering work together more effectively by utilizing an abstraction layer in between the code written by the Analytics team and the code written and maintained by the Software Engineers. By designing applications such that the code written by the Analytics team can be treated as configuration wholly independent from the application code, the two teams can stay out of each others way and work on what they know best.

Some readers may note that this is not actually a novel idea: many companies, especially the really large tech companies (FAANG et al.), invest a lot of effort in making sure their software is architected following this paradigm so that their specialists can be specialized. However, in my work with smaller companies I’ve often encountered an unfamiliarity with or reluctance to utilize this design pattern. In this post I want to make the case that Software Engineering teams should pro-actively look for opportunities to pursue the code as configuration paradigm in order to:

- Unblock their Analytics team

- Improve iteration speed

- Promote specialization (so analysts and engineers can work on what they are independently good at)

- Remove tedious business-logic tasks from the Software Engineering backlog

The Problem

In my work as a data-scientist over the last 10 years, I have written a lot of code. I would wager that the majority of my working time over that period has been spent writing and editing code. Unfortunately, most of that code is, from a software engineering perspective, “bad”. Like many folks working in the data fields, I’m a self taught programmer, and, frankly, writing readable, DRY, efficient code has rarely been a priority for me (“it only has to run once” is a common if frightening refrain among academics and statisticians).

Caveats aside, I consider myself a deeply technical person, but from the vantage of the software engineers I work with, I occupy a bizarre middle-ground: I am technical enough that I can engage with them in architecture discussions, and I know how to use vim, but I very clearly cannot be trusted to write customer-facing production code on my own. Additionally, there is a lot of background knowledge that software engineers are assumed to have like “how the internet works” that I simply do not possess. Occupying this middle-ground of “oddly technical, yet does not understand things” can make it hard to partner and communicate with the broader software engineering organization.

After spending a lot of time collaborating with software engineers with varying degrees of success, I have determined that the optimal pattern for collaboration relies on architecting and building systems where I (and the other data folks on my team) can write and deploy code / scripts without:

- needing to get that code approved by software engineers

- having to deal with hosting or networking concerns

- having to interface with non-familiar languages and paradigms (i.e., I can deploy my R or python code more-or-less as-is).

Programming note: In this document I’m going to use the term “Analysts” to refer to the broader class of data scientists, statisticians, and analysts who may work on a data team but who are not trained as software engineers.

Architecture

To make an application or service like this work, you split your project into two types of code: application code and configuration code.

| Application Code | Configuration Code |

|---|---|

| Runs reliably with logging and alerting | Simple, script-like code or “jobs” |

| Runs on a remote server | Can run and be developed locally (e.g., may be developed in a notebook environment.) |

| Interacts with the internet or other complex objects | Interacts with simple data structures and a local filesystem |

| Handles retries, fault tolerance, etc. | Fails noisily (and sometimes catastrophically), but is isolated |

| Written by software engineers | Written by Analysts |

| Runs the code written by analysts | Is run by the application written by software engineers |

The application code provides an abstracted interface for analysts that allows them to iterate quickly and get their code into production without having to know or understand what the application code is doing behind the scenes.

Pedantic readers1Whom I love. Because I am one of you. may take issue with my terminology here. In particular, the phrase “configuration code” grates on some people who believe that, by definition, running code cannot also be configuration. Bike-shedding potential aside, the terminology is used intentionally to describe how, from the perspective of the Software Engineers, the code written by Analysts can and should be treated as totally separately from their code – from the perspective of their application, the code written by Analysts actually is pure configuration.2When a Software Engineer deploys code to Heroku, how do you think the Heroku engineers think of the code that is being deployed?

Example: The Email Report Processor

Let’s imagine that we want to be able to collect arbitrary reports from an email address (lots of our third-party vendors provide these reports in lieu of API endpoints). While designing the tool for interacting with an email inbox via IMAP may be interesting to a Software Engineer, updating, maintaining, and writing integrations for new reports is definitively not.

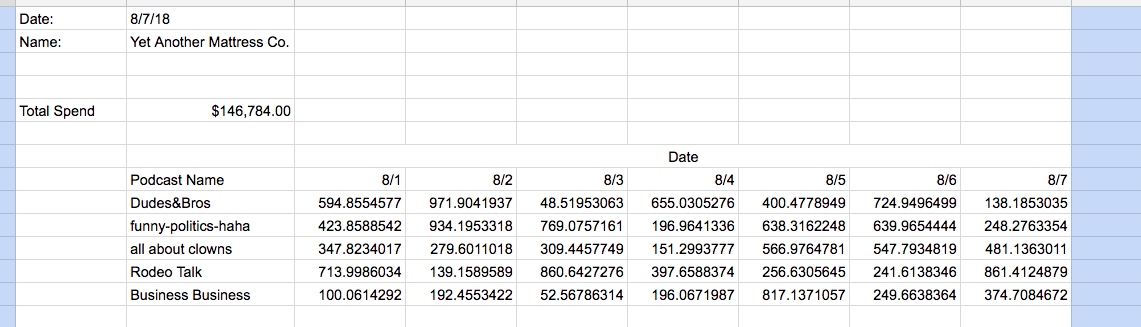

Here’s an example report that has to be cleaned and processed, and is subject to change without warning:

In this report there are blank rows, empty columns on either side of the data, and what amounts to effectively two different tables within one spreadsheet. You can relieve yourself and the rest of your Engineering team from this burden by using the architecture above and letting the analysts maintain this system for themselves.

It turns out that:

- Analysts already know how to do this sort of spreadsheet munging and processing work (and they do it all the time)

- These are reports are naturally owned by an Analyst anyway, and so the Analyst is more motivated to invest time in maintaining it.

Analysts do know how to:

- Read a file off of their desktop

- Munge / cleanse / aggregate the report with the appropriate business logic

- Make use of the data downstream

Analysts do not know how to:

- Get the file off of the email (or even what IMAP is)

- Write their results into a database

- Get their code to run regularly on a computer that is not their laptop3Some enterprising Analysts may already have production cron jobs running on their laptops that you do not even want to know about.

So, a good system will help them leverage what they do know how to do, and will abstract away the things they do not.

| Application Code | Configuration Code |

|---|---|

| Is a coherent application in a single codebase | Scripts that clean / munge different types of email-attached reports |

| Polls the email inbox and parses important metadata (sender, receiver, subject, attachment name) | Maps a sender/attachment combination to a “report processor” script |

| Keeps track of which reports have been processed and which are new | Should be idempotent so it can be retried arbitrarily |

| Reads attachments into memory | Interacts with a dataframe object that’s assumed to be present |

| Handles retries and alerting | May or may not have logging. Fails noisily when something goes wrong. |

| Provides an easy interface with a database for storing processed reports | Calls a simple method to export the cleaned data |

This structure separates concerns nicely: the Software Engineers invest their time in maintaining the abstracted infrastructure that allows the Analysts to work efficiently on processing data and maintaining their own reporting infrastructure. The Analysts can deploy new configuration without bothering the Software Engineers, and the two teams can collaborate on their shared roadmap for new empowering features, rather than throwing tickets “over the wall” to fix broken integrations.

Conclusion

This pattern can be applied to lots of different applications that are commonly worked on by Analytics teams:

- ETL – analysts write the transformation jobs, and there’s a separate app for coordinating and running them (see the paradigm used by dbt and looker)

- ML / Prediction jobs – Analaysts train models with a specified input data source and output data schema, and a separate application marshals and coordinates the jobs, and handles assembling the input data and saving the output data.

And surely there are many more. Remember: Data Analysts are technical folks who write code for (at least) a plurality of the time they are working. You can empower them and take unappealing work away from the Engineering team by designing applications using the code-as-configuration architectural principals.

- 1Whom I love. Because I am one of you.

- 2When a Software Engineer deploys code to Heroku, how do you think the Heroku engineers think of the code that is being deployed?

- 3Some enterprising Analysts may already have production cron jobs running on their laptops that you do not even want to know about.