Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are management tools for monitoring and improving business processes. KPIs are helpful in understanding if you’re hitting your business objectives, improving over time, and helping to forecast future growth. They are also a symbol for folks in the organization to rally around and anchor against, providing clarity and aligning cross departmental objectives.

There is a lot of content out there on what a KPI is (and what a metric is, and what a measure is, …) and why they are important1I won’t be addressing the difference between a KPI, a metric or a measure. Those nuances aren’t relevant to our discussion.. This content is also usually written for non-analysts – useful, but invariably leaves me wanting more. Today I’m going to outline a few key principles related to KPIs aimed specifically at analysts and data scientists. I’ll discuss:How KPIs should be structured within an organizationHow, and why Analytics, can best partner with stakeholders in determining the best KPIs for them

KPIs should fit into the organization’s operational framework

Key Performance Indicators are indicators of progress towards some objective. They are important because they provide direction for folks using them as well as visibility for management to understand how the business is trending.

However, it’s easy to overdo KPIs, e.g., just because some are good, does not mean that more is better. KPIs should be sensible across teams and up-and-down the organization.

KPIs should tell a story

Ideally KPIs should tell the story that your organization wants to tell. KPIs help folks transform a qualitative narrative (“We’re bringing joy to under served communities”) into a quantitative measure (“% of engaged users within the past 30 days”).

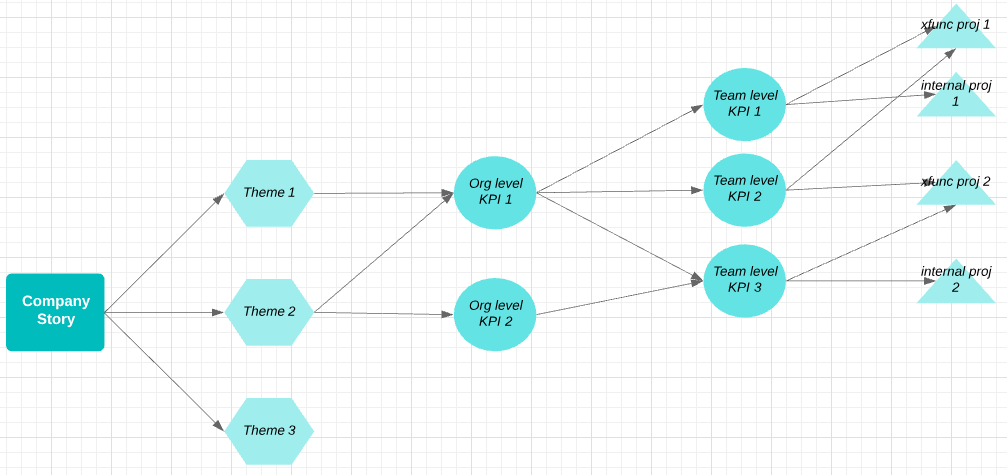

The story should start at the company level and filter down to every team and individual. At each layer there should exist a set of KPIs that are connected, however loosely, like a DAG.

Figuring out how KPIs are related is a useful exercise and ensures everyone is working towards the same goals.

KPIs should makes sense for your organization

Some KPIs may be very specific indeed, and only a few folks on a certain team will care. But as indicated above, every KPI is related in some way to other KPIs elsewhere in the organization. Teams can’t globally optimize in silos. Improving a KPI on one team should not come at the expense of another team. One common example of this is bringing in lots of leads that don’t end up converting down stream. Marketing may be crushing their top line goals but Product ends up overloaded with unqualified users who drop out of the acquisition funnel.

Another example: Finance wants to achieve a specific profit margin in a business line, and they identify some cost cutting measures, which mean that some teams need to change their priorities. Those functions need to work together to determine how they’ll achieve their objectives without creating friction.

Analytics needs to get involved

The Analytics team is best positioned to help teams think about KPIs because:They typically support many operational functions, and therefore have insight into what those functions do and how they’re connectedAnalytics owns, or works closely with, the data model, infrastructure, and dashboarding solution. Analysts should be opinionated as to how KPIs are calculated and how they can be reconciled against each other.

For example, Finance may be looking at cost per acquisition (CPA) by product line and Marketing may be considering CPA by marketing channel. Analytics must ensure that these two KPIs are calculated from the same source of truth and are reconcilable, otherwise folks won’t know which KPI to trust and it’ll add confusion to decision making.

Identify the right KPIs for each team

Once a KPI framework is in place, the analyst should consider how to select the best set of KPIs at each level (Org, Team, Individual). The first step is to identify someone that is ultimately responsible (accountable) for the KPI, even if multiple folks contribute to it. You should find one stakeholder per team or function that will act as your thought partner and KPI owner. Work with this individual to iron out the details about:

- What is the KPI actually measuring?

- How much influence do you have over the KPI?

- What will you do when it varies?

- How frequently should you view it?

Everyone should agree and understand what exactly is being measured

The stakeholder should know exactly what goes into the calculation of the KPI. For example, if you wanted to count the growth in Monthly Active Users, it’s crucial that your definition and calculation lines up with what the business expects.

- Does “monthly” mean past 30 days or as of the end of the previous full month?

- What is an “active user”? At least one click? At least one share? And does everyone on the team agree with this defintion (hint: put this in your data dictionary)?

- How are you thinking about growth? Is it vs. the last 30 days? This time last year?

Make sure you can affect change

Some KPIs are vanity metrics that folks need to internalize but don’t expect to affect much, if at all. Most “All time” numbers qualify as vanity metrics. It’s great to know how many subscriptions you have for PR or morale or for a board meeting, but not very useful in your day to day. Other KPIs are directly affectable. These KPIs are very specific and may only apply to a handful of folks on a given team. Examples include:

- Average page load time

- Number of outages in the past 7 days

- Time between Step A and Step B of the user journey (where A and B are roughly in your control)

- % drop off between Step A and Step B, by relevant cohort

You and the stakeholder directly responsible for the process that the KPI is capturing should use your collective judgement in determining how much influence ya’ll have on the KPI. I wouldn’t bother quantifying the amount of influence, but be intentional about why you think you can change this KPI.

Develop an action plan ahead of time

Now that you’ve identified some KPIs that you can affect and are worth tracking, take the hard step and think about what you’ll do when this KPI does change. Don’t wait for it to double next month before putting together an action plan. I always ask my stakeholders: “If this KPI declines by 10%, will you do anything about it? What about 50%? And if so, what exactly and why?”. This is a good check against having too many useless KPIs. The action plan is key – you’re not asking for a manifesto, just some thoughtfulness and intentionality.

Don’t overreact to every change

Related to the above, just because the KPI varies doesn’t necessarily mean you should react to it. How frequently does your business change in ways that may alter the KPI. Roughly speaking, KPIs that jump around very frequently warrant less reaction than those that show secular increases or decreases over meaningful time periods. Three options you have to better interpret your favorite, excitable KPI:

- Smooth it out. Popular methods include 7 day rolling averages or some decay factor – just make sure that the transformed KPI doesn’t lose too much of its original meaning.

- Be skeptical of % changes – fractions, especially if the numerator and denominator jump around, are extremely hard to pin down. When numbers are small, expect 200% deltas or the like.

- Control for cohorts – this should always be true for time-based KPIs. Remember that cohorts of different ages will mature in different times and make some apples-to-apples comparisons more difficult.

Reviewing KPIs at the appropriate cadence will take a few iterations, but if you pair the affectability of a KPI and have an action plan already, then it’ll help you take a structured approach to understanding and acting on the information if provides.

Conclusion

Everyone wants KPIs, but many folks struggle with articulating the what and the why. Hopefully the above will help you in your conversations with stakeholders and in your own thinking when considering what KPIs are most important for your business.

- 1I won’t be addressing the difference between a KPI, a metric or a measure. Those nuances aren’t relevant to our discussion.