What math education can teach us about using data for strategy

My foremost memory as a Calculus student was the time I watched my precocious, impulsive classmate have a near-meltdown. As a parent of a two-year-old, and with the benefit of hindsight, I assure you, I’m as qualified as anyone to identify it.

My cantankerous classmate was a prototypical math whiz; the type that would churn through integrals and had a knack for applying those slippery trigonometric identities. The exercise that caused them to boil over was learning how to prove the fundamental theorem of calculus. This theorem is the foundational underpinning of the entire field and a staple of calculus education. Whether addressed formally or otherwise, all calculus students are exposed to this theorem early and make use of it often.

What was so disturbing to my classmate about this proof was that its derivation felt entirely foreign compared to the rote mechanics that most textbooks prescribe for developing our mathematical muscles. The proof itself is relatively straightforward, but hinges on a central insight, which ties together two seemingly disparate fields of math in a way that’s not obvious. One might even call it creative. What should have been an awe-inspiring moment for my classmate was instead soaked with despair at the realization that the competencies which made them so successful in their coursework would never have led them to discover this theorem on their own.

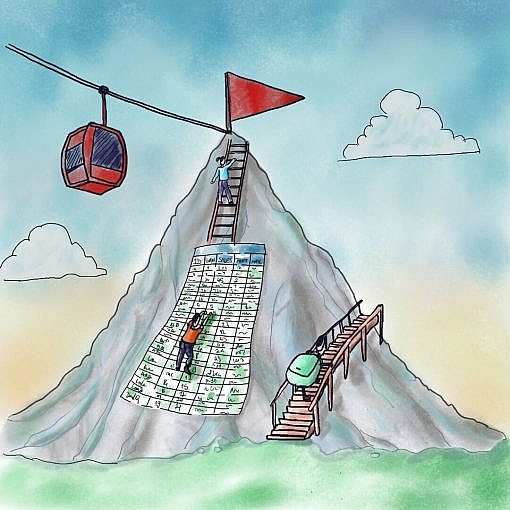

The process of creating new math–that is, proving new theorems–requires a fundamentally different mode of thinking than solving existing math problems. Mastery of mechanical mathematics is necessary but not sufficient. This tension misaligns the expectations of many students and is the result of decades of pedagogy that have cemented the idea that math is an exercise in memorization. There are lessons here about math, education, and creativity, but I think there’s also a strong throughline in the world of data. Emerging from the field of “data mining”, many modern data professions condition their practitioners to regard data as a natural resource, which requires skillful use of machinery to extract and refine, but independently contains all we’re after.

As being “data-driven” has saturated the priorities of so many in business, so too has the demand for data professionals to create new business–to strategize and follow the data to lucrative opportunities. My contention is that just as math students are lulled into believing that repetition and pattern-matching are the key to answering all quantitative questions, a data professional’s traditional toolbox is ill-equipped to produce novel and valuable business strategies due to the limitations inherent to the data available.

The dilution of “insights”

The growth of the data industry over the last decade has ushered in a new generation of data analysts, engineers, and scientists who are more capable than ever. Due to a variety of technical, organizational, and cultural factors, data professionals are producing more reliable pipelines, more rigorous analyses, and more impactful data products. We’ve done so well that in many cases we have assumed a seat at the decision-maker’s table. Given this expansion, and the indisputable usefulness of data all around us, it feels natural1 to look to data to answer the question, “What is the best thing to do next?” The trouble is, data can’t answer that question.

The technical term for the “What should we do?” problem is strategy. In his seminal book on the topic, Richard Rumelt argues that a good strategy begins with an insight which reframes your situation and surfaces new sources of strength. Centered on that insight, the strategy consists of a coordinated set of policies and actions that enable an organization to advance with focused execution. The implication that great strategy depends on deep insight seems like yet another reason for data analyses to set the direction in strategy formation. After all, our industry has risen to prominence on the promise of business-altering insights! Interestingly, however, Rumelt’s description of what constitutes an “insight” is diametrically opposed to how we tend to think of them in analytics.

Colloquially, many analysts refer to a sql query as the input, and an insight as the output. Start with a question, translate it into a query, and report the results. That’s the formula. Rumelt, however, represents an insight as the sort of realization that, by definition, is not the result of some predictable process and cannot be deduced from an existing base of knowledge. To make this case, he metaphorically likens the problems facing a typical business to the “sufficiently complex logical systems” that Gödel proved are impossible to solve in the absence of additional outside information. In other words, they’re less like a puzzle and more like what Treverton refers to as a mystery, which cannot be solved, only reframed. Identifying a true business insight is less about solving for x and more about proving new theorems from scratch.

Causality is the pinnacle in statistics, but a checkpoint in strategy

Certainly, we’d be remiss to conclude that data analyses don’t yield valuable information to the business. Plainly, there are reasons that organizations across all industries continue to invest in the maturation of their data functions. Effective data platforms enable Marketing teams to surgically direct their spending, Operations teams to make their processes more efficient, and Product teams to measure the impact of their features. Organizationally, the most successful companies foster cross-functional alignment around carefully crafted metrics, and commit to exhaustive rituals to monitor them. Decision-makers tasked with defining a company’s strategy are undoubtedly beneficiaries of this quantitative rigor, but a strategy constructed solely on the numbers that describe today’s business is left wanting.

Rumelt incisively argues that most of what leaders call “strategy” falls somewhere on a spectrum between vague ambition and opaque goal-setting. Using historical data to help set organizational targets is an improvement, but Rumelt’s belief is that this sort of positioning only applies a facade to a hollow plan. Instead, he explains that a compelling strategy minimally requires an honest diagnosis of the circumstances, a guiding policy for addressing the challenges, and coherent actions to implement it. It’s tightly coupled with reality.

Selection bias loosens the relationship between the data an organization collects, and the realities of the environment it exists in. There’s potentially a very long list of things that could plausibly help a business achieve its goals–growth, efficiency, innovation–but, its overlap with the things that are represented in trustworthy data is inherently small. An analyst can quickly identify which web page has the best conversion rate, but there is no query that can determine whether overhauling the pricing model will produce more revenue in 3 years time. This is why Tristan Handy writes about how committing to rigid experimentation can be a poor approach for companies that haven’t yet found their product-market-fit. Experiments may help find a local optimum, while what they really need is a “global improvement that’s worth optimizing in the first place.” Even for established companies, any helpful strategy will include non trivial ideas that the market has yet to validate–in other words, much of business strategy exists to help navigate the pre-PMF context.

Traditional statistics aren’t designed to address this selection bias, but implicitly embrace it. Andrew Gelman and Guido Imbens helpfully point out that most statistical frameworks enable us to estimate the effects of causes, while many real-world situations instead call for us to find the causes of effects. Formulating a winning strategy demands that we define the effect we want to generate, and work backwards through the “reverse causal questions” to land on the most promising potential interventions. The statistical applications are not entirely absent, they’re just lighter on theory, and carry a heavier dependence on creative framing and context awareness.

Data can help strategists understand what’s going on to support a diagnosis, it can be used to carry out impact estimates and scenario analyses to inform a guiding policy and its coherent actions, but it’s not infinitely applicable to a world where context is key. As C. Thi Nguyen puts it in his essay, The Limits of Data,

The power of data is vast scalability; the price is context. We need to wean ourselves off the pure-data diet, to balance the power of data-based methodologies with the context-sensitivity and flexibility of qualitative methods and local experts with deep but nonportable understanding. Data is powerful but incomplete; don’t let it entirely drown out other modes of understanding.

Why data professionals are primed to be the best strategists

For all of its strategic shortcomings, data often still gives us the best window into the future. In the modern marketplace, where our products are digital abstractions, downloaded onto devices we don’t own, browsed by people we don’t know in places we’ve never been, we need data to anchor our perspectives. Moreover, the trenches that data professionals occupy guarantee routine encounters with the most puzzling facts about their organization. It’s often not an analyst’s quantitative skills that makes them best at predicting how Prime day will impact sales. It’s the months they’ve spent internalizing which types of transactions are associated with discounts, and reconciling contradictory sales totals. These experiences form one’s mental model of their business, and prepare them to think flexibly about new initiatives. As Csikszentmihalyi points out in his illuminating book on creativity,

…insights tend to come to prepared minds, that is, to those who have thought long and hard about a given set of problematic issues.2

In 2011, David Bressoud wrote an article for the American Mathematical Monthly, which offers an instructive perspective on the historical circumstances that led to the discovery of the fundamental theorem of calculus. In it, he untangles the narratives of the crowd of characters that contributed to this academic feat, across hundreds of years3. As diamonds require time and pressure to be formed, he conveys how this mathematical reality took time and genius to be expressed.

Calculus emerged because the geometric and dynamic conceptions of the integral and derivative came to be seen as manifestations of common general principles, but it took time and genius to extract those general principles.4

Under a long enough duration, having a directed focus and a curious mind can give way to genius, even among the ordinary. The demands of the data profession require its constituents to face the facts of its organization each day. Great analysts embrace this process and use it to iteratively tune their beliefs. They’re moored by the objectivity of the data, but balance its biases by keeping curiosity at the fore. There remains no formula for great strategy, but clues about its components are readily available to the data professional, priming them to be strategic catalysts.