After last week, I hope you’re on board that a career ladder is important, so let’s jump right into creating one that works for your team. This post will walk you through the two key parts of a good career ladder – guiding principles and specific competencies – and will point you toward some examples of ladders others’ have created for inspiration, including the career ladder my own team uses.

This is part 2 of a series on career ladders – you may want to read part 1, why a career ladder is so important, before proceeding and follow it up with part 3, how to use a career ladder once you’ve got it.

Find Your Guiding Principles for Levels

Guiding principles are simple heuristics that capture how roles differ from each other. You don’t get promoted for just getting better at the same job, you get promoted for showing that you can do a different job – or in many organizations, that you’ve already been operating at the next level for some amount of time.

Some examples of guiding principles:

- A general management heuristic we use at Yerdle: a Manager executes a program with some direction, while a Director can create a program from scratch.

- Software Engineering at Microsoft: a Software Engineer creates complex solutions to simple problems, a Software Engineer II creates simple solutions to simple problems, a Senior Software Engineer creates simple solutions to complex problems, and a Principal Software Engineer makes complex problems disappear.

- Design at Lyst: Junior contributes to the work, Mid does the work, Senior leads the work, and Lead leads the team.

- Data Science, according to Jan Zawadzki: Level 1 data scientsts have strong statistics skills, Level 2 adds engineering skills, and Level 3 adds business skills.

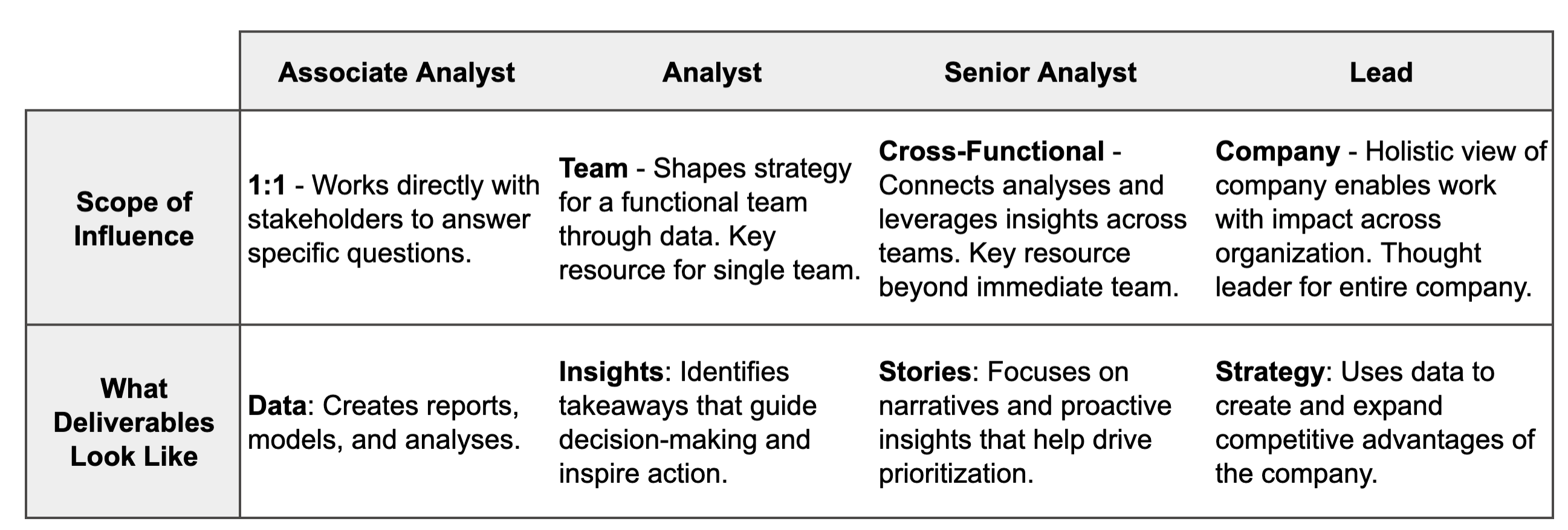

My own principles are not so pithy. When I think about how analytics team members work at different levels and how to clearly articulate the difference between roles, there are two key areas where I see step changes with experience: scope of influence, and what deliverables look like. Here is my matrix for those principles for individual contributors:

These principles are the key to communicating the need for promotions outside your team (to your manager and other senior managers), so I very intentionally focus most on areas that are visible outside the analytics team and that clearly impact stakeholders. We’ll get to technical proficiency a bit later – it’s an important part of the role, but often significantly harder to communicate to those who have to buy into promotions for my team.

Guiding principles align levels across the team, setting the stage for the role-specific competencies that come next. These consistent principles enable you to create flexibility and variations of the ladder as needed. You can modify a career ladder for various flavors – if your team includes data scientists, analytics engineers, data product managers, data engineers, or other roles, your guiding principles should work across disciplines, providing continuity in levels as well as making the path between specialties clearer. You can even modify a career ladder for a single individual who wants to follow a specialist path if that makes sense for the team. I manage fairly small teams and am happy to accommodate different career paths; knowing the guiding principles has allowed me to create a Product/UX Analyst ladder and a Sales Operations Analyst ladder that spoke to the skills and roles of particular individuals more specifically, but still aligned very clearly with the team’s overall leveling framework.

Levels and Timelines

I’ve found that it’s helpful to think about how long it will take someone to demonstrate all of the competencies necessary for their next level, and to have that change as you move up the ladder. Junior roles should enable a promotion within a year of starting the role. Mid level roles may require a couple of years to demonstate the full breadth of skills. Senior roles can be career level – you may be in that role for several years or longer before advancing. Considering those time frames while you are creating the ladder will make it much easier to communicate expectations to your team as you roll it out.

Get Feedback From Key Decision Makers

Guiding principles are a great level of detail to share broadly within your company to help create role alignment across teams. At a minimum, solicit feedback from your manager and your human resources team to make sure that the roles you’re proposing align with an overall company leveling strategy, to the extent there is one. Some companies tend toward very well-defined ladders with many levels, while others have fairly flat structures with fewer levels. You’ll need to align with that strategy, and if your company has a solid software engineering career ladder, I find it helpful to align as much as possible with the number of roles and types of titles that team uses.

The guiding principles are also helpful in framing the answer to two key questions that come up at promotion time – why does the organization need a higher level role, and why is this person ready for that role? Aligning with the company overall on the precursors to those questions – why would the organization need a higher level role, and what makes a person ready for that role – will be a good investment for future promotion discussions.

Ladder Specific Competencies in Line With Your Principles

Once you identify your guiding principles, you can flesh out the skills and behaviors associated with each level. These should be specific enough to guide your team’s behavior, and concrete enough to enable provide an objective measure of success. I focus on a few main types of skills, then provide several examples of how a person can demonstrate competency at each level. Those categories are:

- Technical skills

- Analysis and business acumen

- Operational skills

- Mentorship and training

- Communication & interpersonal skills

Specific competencies are where it is most useful to get feedback from your team – the people who will be measured against this ladder. They can help you ensure that skills are associated with the right level, and importantly, that the ladder captures all of the types of work that they spend a significant amount of time on. This process ensures all valuable work is promotable, to minimize glue work on your team.

It can be tempting to try to make expectations measurable to make them more objective – for example to spell out exactly how many pull requests someone should be creating or reviewing each week. But so far, I haven’t found any skills that can meaningfully be measured in this way. Commits, lines of code, PRs, or any count of analytics deliverable can be gamed, and I’d rather have folks focus on the quality of their work than the quantity. As a result, there is always some amount of subjectivity in evaluating performance against these skills – but the clearer the expectations, the more useful in guiding behavior and shaping conversations about performance.

Given how significantly analytics has changed over the past few years, and how quickly we continue to adapt to a more engineering-oriented mindset, these competencies are likely to continue to change over time. Stay open to your team’s feedback and revisit the ladder periodically to make sure you’re capturing the work and skills you most want to see on your team.

Put It All Together

So you want to actually see a ladder, right? The ladder we use today at Trove Recommerce is publicly available, and I encourage you to leverage it as a starting point for your own. We are a fairly small team (5 total), primarily individual contributor analysts. As such, my IC ladder is much more robust than my management ladder. If your team is more data science-focused, there is a good ladder in Care and Feeding of Data Scientists to get you started.

For other examples, as usual, it’s helpful to take a look at software engineering, where they’re a couple of decades ahead of us in terms of management craft. The thoughtful engineering ladders from Spotify, Etsy, and Rent the Runway were helpful as I created this and prior iterations of my team’s career ladder. Julia Evans also has some really great thoughts on the fundamental differences between an Engineer and a Senior Engineer.

Another team’s career ladder is a great reference, and I’m sharing our ladder specifically because I don’t think anyone should have to start from scratch. That said, I’d encourage you to spend some time and effort personalizing any ladder you borrow to fit your team. Your ladder should reflect your priorities for your team – where is the optimal balance between technical work and stakeholder-facing work? What are the softer skills that are necessary to succeed within your company? How much specialization do you expect from your team, and at what point in their development? Rolling out a ladder that doesn’t quite fit can be worse than not having one at all – your team thinks expectations are clear, but there are still implicit expectations to navigate.

Now What?

Once you’ve got a career ladder, a thoughtful rollout and effective use of it can make the difference between something that you send to new hires and then never come back to, and a tool that shapes employee development and sparks valuable conversations all year long. Part 3 digs into how to use the ladder you’ve built, and what to do if you are an individual contributor who doesn’t have a career ladder. I would also love to hear from you – what are the guiding principles that define roles for your data team? Are there skills that have become more or less important to advancement in the last few years? And if you have a publicly available career ladder for your data team, I’d love to link to it! Send me an email or come have a chat in our Slack channel!