In 1931, an Indian mathematician and librarian named S. R. Ranganathan published The Five Laws of Library Science. In the preceding century, libraries had undergone what he characterized as a revolution. Before then, librarians had effectively been tasked with protecting books from all but the most privileged readers–medieval texts were literally chained to the shelves. But the rise of democracy, alongside advancements in technology that made it easier to copy and distribute information, was inspiring communities around the world to expand access to books. Major figures like Andrew Carnegie were betting that investments in the literacy of the masses would yield great economic and social returns.

This paradigm shift prompted the development of new architectures and lending policies that allowed patrons to browse the collection for themselves and even take books home. The role of librarians was professionalized: training programs and best practices emerged for how to secure funding, assess the community’s needs, select and catalog materials, and so on.

These conditions probably sound familiar to data professionals in 2024.

Before I managed a data platform, I earned a Master’s degree in Library & Information Science and served on a team of librarians at a global investment firm for almost a decade. While I’m certainly not the first to make a connection between librarianship and data work, my experience has proven that the parallels run deep. Data professionals and librarians share the noble goal of organizing and disseminating knowledge for the good of all. We have many skills in common, the complexity of our work is often underestimated by those who are unfamiliar with it, and we are both regularly asked to defend ourselves.

The Five Laws of Library Science comes to the rescue with a lively argument for the library as a locus of financial leverage and a matter of societal interest, as well as a pleasant place to spend time. Librarians have since survived the inventions of digital computers, the internet, and Google, despite the critics who proclaim our obsolescence. While his book does not answer the tactical questions of modern data management, Ranganathan did identify a set of grounding tenets that any data leader would be wise to embrace. I have translated them for our purposes here, leaving Ranganathan’s words as direct quotes.

First law: Books Data are for use

The first law asserts that the storage and processing of data are only valuable insofar as they support the use of data. Put differently, when we have a choice between what we call data governance and data enablement, we should optimize for enablement.1 Ranganathan sees this as trivially obvious, but he knows we prefer to be left alone to focus on the deep work of tidying up our data.

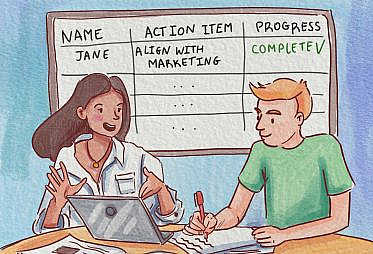

He insists on user-centricity: we must create welcoming experiences that invite people to use data. While he allows that interruptions and “unreasonable” stakeholders are frustrating, he urges us to summon patience. Everyone brings a blend of business context, numeracy, information literacy, technical skills, external influences, incentives, and insecurities to their interactions with data. Instead of convincing them that our way is always best, we should seek to understand what drives someone’s decisions and guide them to the resources that are fit for their use case. The librarian’s version of requirements gathering, the reference interview, was designed to build trust that we will be available to help anyone find a solution, even if we don’t have it ready on the spot or if they don’t choose our preferred method.2

If we are staffing our data teams for enablement, Ranganathan advises us to hire for subject-matter expertise and technical proficiency, yes, but especially “personality, tact, enthusiasm, and sympathy.” We must all take a genuine interest in the people who will use the data. We should learn to speak our stakeholders’ language, so that they can articulate their needs and pain points to us in their own terms and feel heard. We should position ourselves as a “friend, philosopher, and guide” to the organization, partnering with stakeholders as equals to push the boundaries of our knowledge together.3

Second law: Every reader stakeholder his or her book their dataset

The second law doubles down on democratization: to unlock the full economic value of data, organizations should empower everyone to use it, not just specialists like business analysts and data scientists.

Ranganathan argues that you cannot simply open up access and declare victory. Consider the Little Free Library, a well-intended “self-service” library implementation that still requires a sponsor for setup and basic maintenance. These libraries famously attract the worst books in any neighborhood, while the most desirable books remain siloed in individual homes and used rarely or shared only within networks of friends.

To achieve real success, just as in a political democracy, everyone has to play an active role:

- Leadership provides funding and coordination. Ranganathan endorses a federated or “hybrid” model, with a central team to handle shared infrastructure and expenses, specialized teams aligned to stakeholders in each domain, and interfaces for collaboration between them. The equivalent is a central city library with neighborhood branches and an interlibrary loan program.

- Data leadership sets a strategy for the data to be managed cost-effectively and hires a strong team that is aligned to a mission of enablement across the organization.

- Data team members develop familiarity with all of their stakeholders, business concepts, data sources, and data policies, in order to provide support efficiently.

- Stakeholders recognize that the data team exists to enable their use of data, not to inconvenience them, and that its tools and policies are designed to benefit the organization and their fellow users.4 They should take full advantage of the resources, but only request exceptions that are justified by a business objective rather than a personal preference or a false sense of urgency.

Ranganathan assures us that if our leaders and stakeholders see their own interests reflected back at them when they look at our data team, questions of resourcing become much easier to resolve.5

Third law: Every book dataset its reader stakeholder

The third law reminds us that we will need to advocate for the use of data. Especially given a pivot from governance to enablement, our stakeholders might not realize what they can get from data or understand how to work with a data team, even if they have the right access.

Ranganathan recommends a variety of proactive measures (adapted here) to connect people with data and maximize usage:

- Architect and organize datasets intuitively6

- Enrich and expose metadata to support discovery and provide context

- Reach out to stakeholders with updates of possible interest to them

- Draw people in with fun and approachable datasets

- Host programming, e.g. onboarding and instruction sessions, demos, speaker series

Regardless of the methods we choose to promote data, we are advised to “bear in mind the general principles of publicity, such as continuity, variety, novelty, clarity, and personal appeal.” Who among us hasn’t started a generic newsletter that slowly petered out? Tailoring communication to your audience and showing a sense of humor can go a long way.7

The other implication of the third law is that when a dataset or tool has no users, despite our best efforts to promote it, we should retire it to reduce administrative and mental overhead. Librarians call this “weeding”–culling (or moving off site) materials that patrons no longer require to make room for new offerings. Curating the collection like this keeps it fresh and relevant.

Fourth law: Save the time of the reader stakeholder

The fourth law recognizes that our stakeholders must be able to find and benefit from data quickly for the organization to realize its value. Providing direct access is an important step, but we should continuously observe our users and seek opportunities to shorten the paths from needs to solutions.

Ranganathan suggests two complementary approaches to saving the user’s time:

- Build self-service tools, taking advantage of automation and established standards to save the time of the data team as well. Librarians have developed innovative signage, online catalogs, self-checkout kiosks, and applications like Libby so that patrons can access materials independently.

- Provide support via multiple channels and, where appropriate, embed solutions or analysts in existing business processes–even if that means working in spreadsheets or operational systems sometimes. The bookmobile is an enduring example of how librarians go out of their way to meet people where they are.

Ranganathan also takes care to point out that good user experience design at scale is deceptively hard, and that technical solutions require investments in people and process behind the scenes: “[someone] has to devote his thought to such problems and solve them.” He stresses that leveraging the attention of a few expert staff will pay dividends by saving the time of many across the organization.

Fifth law: A library data function is a growing organism

The fifth law promises that if we follow the first four laws, data leaders should expect dynamic results and plan for growth along two dimensions over time:

- An increasing quantity of data, stakeholders, and team members to manage

- An ongoing evolution of our form–the datasets, tools, and services that make up our function

The implication is that in order to grow, we will have to continue renegotiating our boundaries and navigating new technology…forever. If this sounds daunting, I encourage you to channel Ranganathan’s energy. Speculating about the future of his beloved libraries as he closes the final chapter, he asks cheerfully, “Who knows that a day may not come…when the dissemination of knowledge…will be realised by libraries even by means other than those of the printed book?”

Something tells me he would have loved running a data team.

Footnotes

- Note: This is not a rebranding–it’s a call to compromise on governance for the sake of usage when our legal and ethical obligations permit. Laura Madsen takes a similar position in Disrupting Data Governance. ↩︎

- Jenna Jordan has a post about this in her drafts, so I’ll refrain from exploring it further here. Update August 2025: The librarian’s reference interview for data teams. ↩︎

- As a team, he adds later, we should embody “the spirit of the hive,” with egos “suppressed to such a degree that every member is prepared to pass off all work as anonymous.” ↩︎

- This must ring true to them–recall that the first law asks us to ease up on governance when we can afford to. ↩︎

- The clearer the organization’s identity and vision for itself are, the more accurate this reflection is likely to be. ↩︎

- For example, Ralph Kimball designed dimensional modeling to make data models more legible to both engineers and business users. You can also imagine the list of objects in your data warehouse as a shelf, where logical arrangement (and labeling) enables discovery by proximity. ↩︎

- Librarians often collaborate with educators in this domain, and former teacher Faith Lierheimer demonstrated these ideas expertly at Coalesce 2023 with “Analytics in Bloom: Improve your team’s data literacy with pedagogy.” ↩︎

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Deb Seys for the inspiration to revisit The Five Laws, to Susannah Barnes for introducing me to Deb, to Margarita Fomenko for the illustration, and to Jenna Jordan, Neil Zimmerman, Caitlin Moorman, and Emilie Schario for their editorial contributions and support.